Self-hosted GPT: real response time, token throughput, and cost on L4, L40S and H100 for GPT-OSS-20B

We benchmarked modern open-source LLMs across several popular GPUs to measure real-world context limits, throughput, latency, and cost efficiency under varying levels of concurrency — as close as possible to real production conditions. Here we share the results.

LLMs are now an inevitable part of every successful business. When used correctly, they can dramatically increase technology ROI.

More and more companies of all sizes are already using LLMs across many aspects of their operations, but the key concern they raise now is: “Where does our data go?” As a result, many organizations have started considering hosting LLMs locally.

The market already offers high-quality LLM models (OpenAI GPT OSS, DeepSeek, Mistral, Qwen, and many others), but the real questions are: what are the limits, how much throughput can you achieve, and at what cost? In this post, we provide clear answers.

Shadow AI issue

A short quote from the OpenAI Privacy Policy: https://openai.com/policies/row-privacy-policy/

We collect Personal Data that you provide in the input to our Services, including your prompts and other content you upload… We may use Personal Data to provide, maintain, develop, and improve our Services… We may disclose Personal Data if required to do so by law or in response to valid legal requests by public authorities.

Public ChatGPT is not a confidential or legally privileged channel, it’s a commercial service governed by its Terms and Privacy Policy.

This drives Shadow AI: employees using unapproved tools and sending sensitive data (contracts, code, financials, PII, strategy), increasing leakage, compliance, IP, auditability, and legal discovery risk.

Strategy 1: Build your own tooling using LLM APIs

Using LLM APIs (e.g., OpenAI) to build internal tools is generally safer than public SaaS and helps reduce Shadow AI, but it still requires governance. API data is typically not used for training by default and may be retained for abuse monitoring (often up to ~30 days), and it can still be disclosed under legal requests or affected by policy changes.

Strategy 2: Sovereign AI self-hosting on Local Hosting Provider

A “local” provider (in the same country/region and legal jurisdiction as your company) under a signed DPA can reduce data exposure and improve jurisdictional control (clearer legal recourse than cross-border setups), but it does not eliminate disclosure or operational risk.

This aligns with sovereign AI concept which means jurisdiction-level control over AI infrastructure, data, and operational governance — ensuring models are managed within a defined legal and regulatory framework. In this context, working with a local provider can be viewed as a practical step toward jurisdictional sovereignty, even if it does not amount to full-stack national AI autonomy.

Strategy 3: Self-hosting using on-premise hardware

Running LLMs on fully owned on-premise hardware further reduces third-party exposure. Controlled physical access and isolated infrastructure maximize data locality and remove dependence on external AI or cloud providers.

Absolute zero risk does not exist but on-premise deployment reduces third-party trust assumptions while shifting full responsibility for security, resilience, and compliance to the organization.

Hardware requirements for LLM self-hosting

Self-hosting a model on custom hardware is not technically complex for professional software dev companies like DevForth, but the important factor is understanding the limitations, which mainly depend on the hardware. So here we will try to measure them using the gpt-oss-20b model from OpenAI on different hardware and with different vLLM params.

To understand every term in what follows, I strongly recommend reading my LLM Terminology explained simply post

For LLM inference, GPU VideoRAM is usually the main bottleneck: it must fit both model weights and the KV cache (which grows with effective sequence length and with the number of concurrent requests). Running LLMs on CPU RAM downgrades performance typically to 100× - 1000× slower, with TTFT becoming painfully long.

For production-grade LLM hosting, the practical VRAM window usually lies between 24 GB and 80 GB. Yet memory size alone does not guarantee viability. Throughput, tensor performance, memory bandwidth, and platform support often make the decisive difference. For that reason, we consider only GPUs with demonstrated, real-world performance.

Very rough planning price ranges (vary by region/availability): 24 GB GPUs like RTX 3090(350W), RTX 4090 (450W), or L4 (72W - much better for server) are typically €200–€1200/mo to rent and €700–€3500 to buy; 48 GB (L40S) (350W) is often €1000–€1600/mo and €7k–€11k to buy; 80 GB (H100) (700W if SXM or 400W PCI) is roughly €1500–€2500/mo and €18k–€45k to buy.

Benchmark and self-hosted OpenAI GPT OSS software setup

We set up a self-hosted vLLM in Docker as the inference engine for our experiments.

- In each experiment, we take a portion of Moby-Dick (Herman Melville, plain text) and ask the model to return a summary in JSON format.

- We add a secret code in the first pages of the book and ask the model to find it, to ensure it is still using the full content.

- We always add a random number at the beginning to prevent vLLM from using prefix caching (we’re interested in the worst case).

- At each point, we run two checks: whether the response is good and parseable, and whether the secret code is correct. Since availability/parseability issues can generally be retried, we do up to 3 retry attempts in case of JSON errors. If the result is good on the first try, you’ll see a green point on the chart; if it was retried, you’ll see a yellow point; if all attempts fail, we stop the experiment and mark that point red in the charts (no sense in continuing).

- If the output is parseable but the secret code is not detected/correct, you will see a red point and we stop the experiment, because this kind of sense loss can’t be fixed by retries and means model degradation.

We always run all requests to vLLM with the same parameters:

reasoning_afford: "medium", // reasoning affordance

max_tokens: 1536, // max_tokens

temperature: 0.15,

top_p: 0.9 Here is example JSON which we received:

{

"status": 200,

"streamedResponse": {

"main_theme": "The obsessive quest for the white whale and its destructive consequences",

"key_characters": [

"Ishmael",

"Captain Ahab",

"Starbuck",

"Queequeg",

"Moby Dick"

],

"causal_events": [

"Ahab's vow to kill Moby Dick",

"The crew's moral conflict",

"The final battle with the whale",

"The ship's destruction"

],

"hidden_implication": "The story critiques the hubris of humanity in confronting nature",

"secret_code": "314781-21"

}

}Structured output mode

We executed all our experiments in Structured output mode. In two words, this is an API-level setting that asks vLLM to respect an output JSON schema at decoding time.

Modern structured output modes (like those in vLLM or OpenAI-compatible APIs) don’t just say to the model “please produce correct JSON” — they actively constrain generation at the token level. Under the hood, the model still produces logits (raw probabilities for every possible next token), but the runtime system masks out any tokens that would break the expected structure (for example, invalid JSON syntax at a given position). Sampling with temperature or top-p then happens only over the allowed tokens. This makes invalid outputs effectively impossible rather than just unlikely.

In production, this is critical: it dramatically reduces malformed responses, eliminates most retry logic, and significantly improves consistency and adherence to the required schema. If you naively prompt a model to “return valid JSON,” it will work most of the time — but occasionally (say 1 in 100 responses) you’ll still get broken JSON and need to retry. Structured decoding avoids that class of failures, which is why it’s essential for reliable, production-grade systems.

And vLLM supports it!

How we started vLLM

We used a plain Docker container deployed via Terraform to a GPU server:

docker run --rm \

--name gpt-20b \

--gpus all \

--ipc=host \

-e HUGGING_FACE_HUB_TOKEN=${var.hf_token} \

-p 8000:8000 \

vllm/vllm-openai:latest \

--model openai/gpt-oss-20b \

--dtype bfloat16 \

--kv-cache-dtype fp8At the time of this research, the latest version of vLLM is 0.15.1.

Besides the explicit parameters, there are many implicit ones under the hood. Several important parameters that may be worth tuning are below. We intentionally left them at default values, since vLLM defaults are a good starting point for many tasks.

For our clients’ setups, starting from recent versions of vLLM, we use defaults as they are battle-tested and OOM-safe.

| Docker command param | Default | Description |

|---|---|---|

| --gpu-memory-utilization | 0.9 | Max fraction of VRAM vLLM can use for weights, KV cache, and activations; recommended values are 0.9-0.95 if we run one vLLM per GPU. The remaining ~5%-10% is needed for overheads; if you don’t leave enough headroom, you will hit OOM (out-of-memory). |

| --max-num-batched-tokens | 2048 | Upper bound on the total number of tokens processed in a single scheduler step across all active sequences. If exceeded, the scheduler splits the workload across multiple forward passes. Trade-off: with lower values, TTFT grows because you need more forward passes, but decoding speed can increase. |

| --max-model-len | 131072 | Maximum allowed ESL. Must not exceed the model’s architectural context window, which is the default (128 Ki tokens per gpt-oss-20b) |

| --max-num-seqs | 256 | How many parallel active sequences vLLM can handle. If it is set to 1 and two requests arrive close in time, the second request is queued and the user waits for the full prefill and full decode of the first request. Increasing this does not generally cause OOM, but actual parallelism may be limited by VRAM capacity. |

Max effective sequence length benchmark (input + generated tokens)

On every sequence run, the model takes the whole prompt (including, for example, system messages, history messages, summary, and RAG context) and then generates output from it. For reasoning models, it first generates some amount of “thoughts” in the output and only then generates the real response.

The sum of the actual input and output tokens is called the effective sequence length. The actual effective sequence length can’t be larger than context_window. Example context windows:

- Proprietary GPT-5 mini - 400k tokens

- Open gpt-oss-20B - ~131k tokens (128 Ki tokens)

- Open gpt-oss-120B - ~131k tokens (128 Ki tokens)

- Open GPT-J which we self-hosted in 2022 (GPT 3 Davinci analog) - ~2k tokens (2 Ki tokens)

So here’s what we do in the experiment:

- In each experiment, we take the first N words from Moby-Dick and ask the model to return a summary. We slice text in words, but on charts you will see actual tokens.

- We increase the prompt in large steps (e.g., 5k words per point) and measure how fast it generates results and whether the result is correct.

- We see the real maximum sequence length and time to first token (TTFT).

In this test, we never run parallel requests: we wait until the first one finishes before starting the next (single-user emulation).

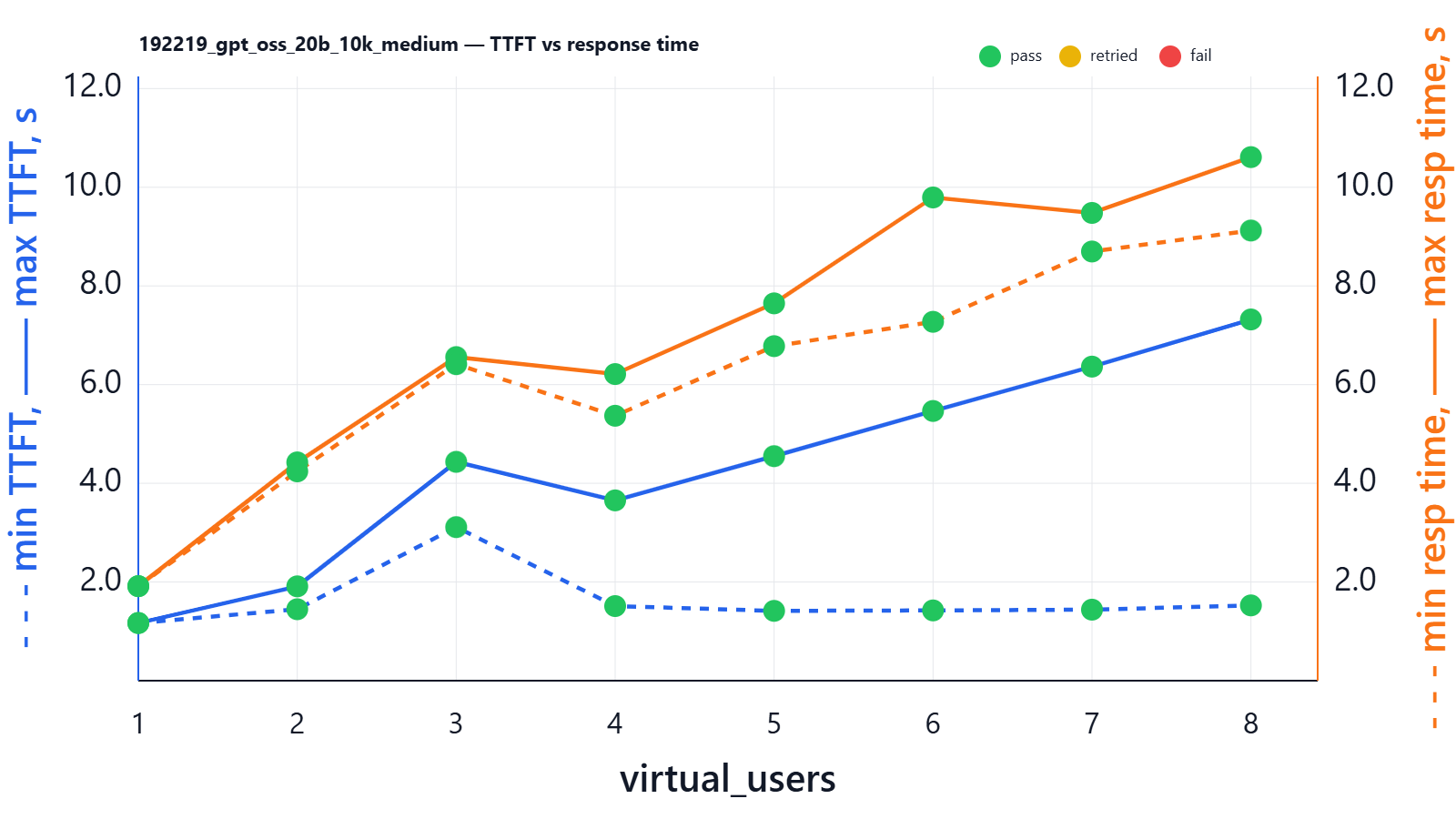

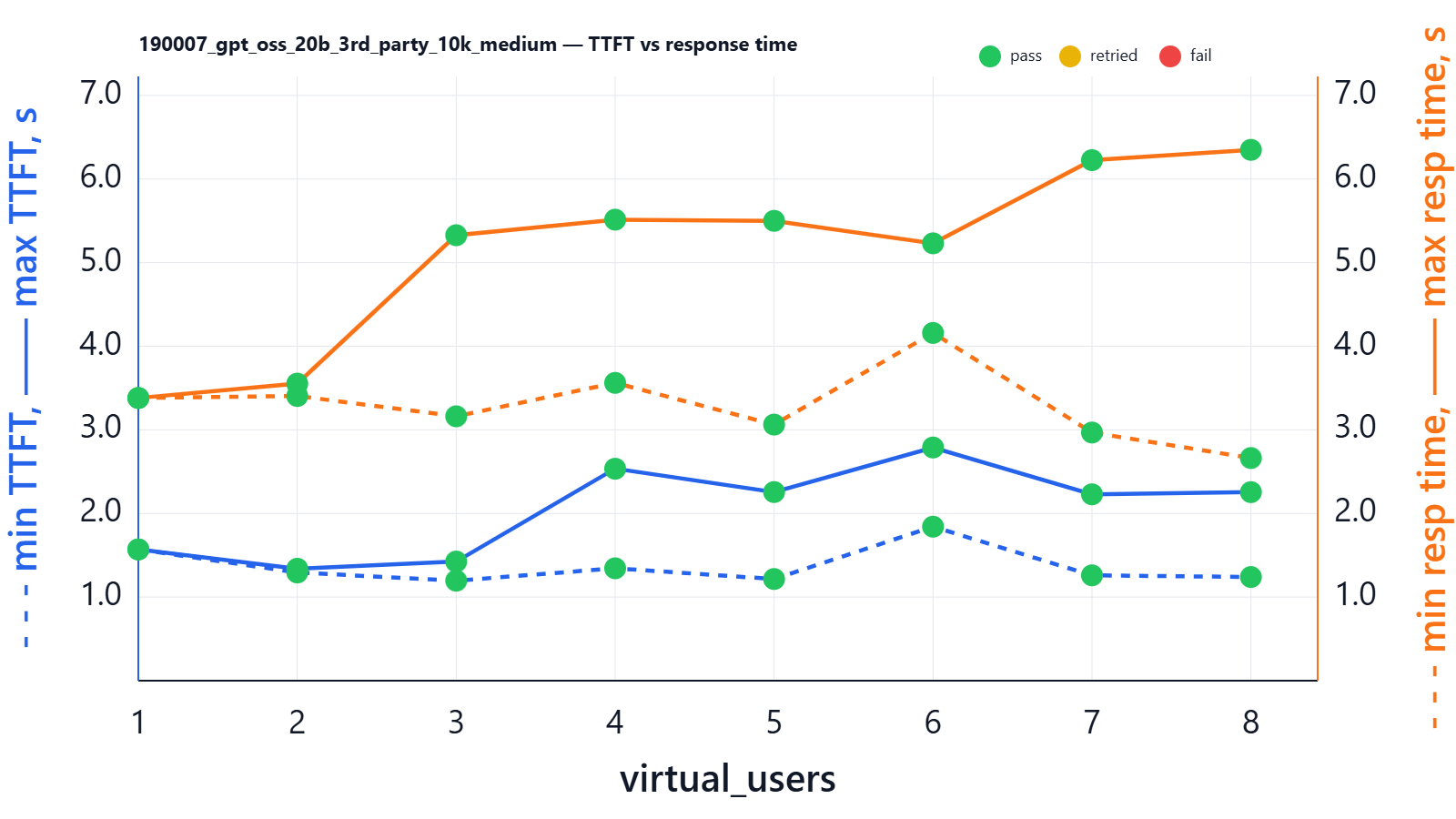

Ability to handle parallelism benchmark (multiple users wait time)

In another test, we take a fixed point (10k input words—a fairly typical RAG/agent workload) and simulate requests from parallel users.

This is like several users using the model at the same time, and we observe how the average per-user throughput and response time react. In the previous example we measured decoding throughput (the speed at which tokens are generated after the first token is received).

In this test it’s more interesting to look at min/max TTFT and min response time (for the most “lucky” user) versus max response time (for the most “unlucky” user). Difference in time between the most “lucky” and the most “unlucky” user is a good proxy for how well the model can handle parallel requests without letting some users wait too long.

L4 24G

Typical rental price for server with L4 1x24G assuming mid-range stable on-demand: €520–€1175 / mo higher ones closer to Enterprise-grade hosters.

If you want to have it on premises

You can insert it in some GPU-capable rack server (2U-height) with full-height slot for Video card like Dell PowerEdge R730 (1000) and connect it to your network.

You can insert it in some GPU-capable rack server (2U-height) with full-height slot for Video card like Dell PowerEdge R730 (1000) and connect it to your network.

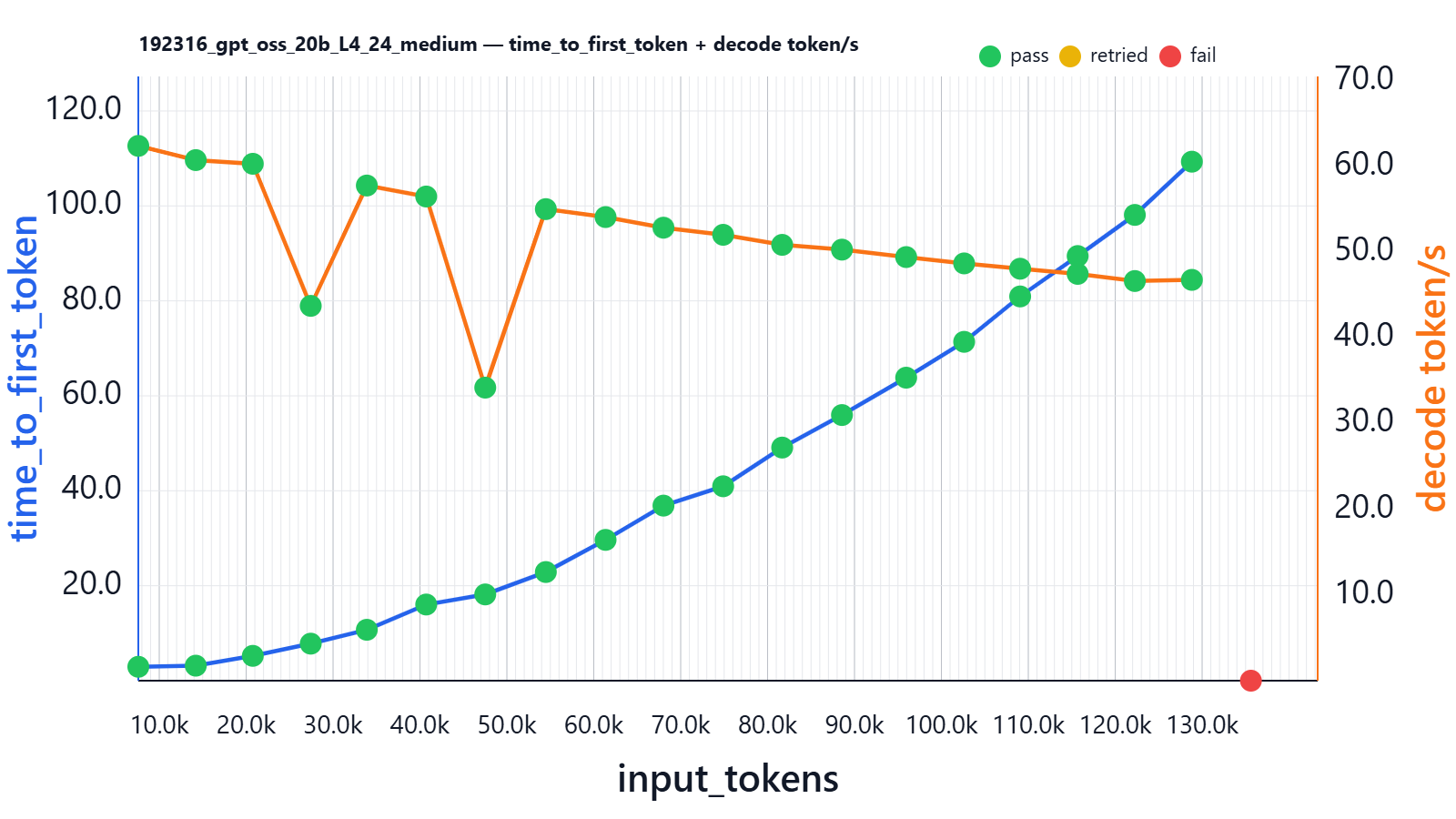

Here is a sequence-length benchmark result:

| input_tokens | thinking_tokens | output_tokens | effective_sequence_length | time_to_first_token | decoding_tokens/s | thinking_time | Json_test_ok | secret_test_ok | nonempty_test_ok |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7591 | 144 | 63 | 7912 | 2.926 | 62.387 | 2.251 | pass | pass | pass |

| 14203 | 205 | 67 | 14537 | 3.160 | 60.728 | 3.227 | pass | pass | pass |

| 20765 | 105 | 90 | 20993 | 5.228 | 60.297 | 1.749 | pass | pass | pass |

| 27431 | 245 | 81 | 27740 | 7.800 | 43.723 | 5.918 | pass | pass | pass |

| 33884 | 159 | 52 | 34043 | 10.718 | 57.761 | 2.810 | pass | pass | pass |

| 40717 | 107 | 100 | 40810 | 16.042 | 56.480 | 1.910 | pass | pass | pass |

| 47511 | 67 | 99 | 47513 | 18.169 | 34.185 | 1.187 | pass | pass | pass |

| 54483 | 71 | 86 | 54420 | 22.886 | 55.011 | 1.265 | pass | pass | pass |

| 61357 | 62 | 93 | 61266 | 29.654 | 54.082 | 1.103 | pass | pass | pass |

| 68018 | 97 | 140 | 67941 | 36.872 | 52.843 | 1.894 | pass | pass | pass |

| 74886 | 107 | 92 | 74717 | 40.947 | 52.013 | 1.918 | pass | pass | pass |

| 81677 | 85 | 187 | 81546 | 49.100 | 50.841 | 1.731 | pass | pass | pass |

| 88556 | 48 | 147 | 88273 | 55.950 | 50.284 | 1.007 | pass | pass | pass |

| 95944 | 104 | 107 | 95611 | 63.822 | 49.415 | 1.991 | pass | pass | pass |

| 102616 | 107 | 99 | 102194 | 71.371 | 48.677 | 2.153 | pass | pass | pass |

| 109060 | 58 | 167 | 108596 | 80.934 | 48.056 | 1.326 | pass | pass | pass |

| 115676 | 111 | 95 | 115147 | 89.445 | 47.455 | 2.119 | pass | pass | pass |

| 122257 | 83 | 115 | 121669 | 98.105 | 46.621 | 1.719 | pass | pass | pass |

| 128819 | 59 | 119 | 128175 | 109.318 | 46.756 | 1.324 | pass | pass | pass |

| 135614 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | fail | fail | fail |

Time to first generation grows non-linearly and reaches ~109 seconds for a ~130k-token prompt. Decoding speed falls from ~60 to ~45 tokens/second.

VRAM at this experiment is stable and reaches 21.725Gi/22.494G.

The two decoding-speed drops are most likely caused by internal attention-kernel switching inside the inference engine. As the input sequence length crosses certain thresholds (around ~30k and ~50k tokens), the runtime switches to different CUDA/FlashAttention kernel variants or GEMM configurations optimized for larger context sizes. These transitions can temporarily reduce SM occupancy or change memory access patterns, resulting in a brief throughput dip before stabilizing again. Since this happens with a single request on an otherwise idle GPU and the performance trend recovers immediately afterward, it strongly suggests a kernel-boundary effect rather than memory pressure or resource contention.

What about ability to handle parallel users? On model load we saw the following in vLLM logs:

Your GPU does not have native support for FP4 computation but FP4 quantization is being used. Weight-only FP4 compression will be used leveraging the Marlin kernel. This may degrade performance for compute-heavy workloads.

Maximum concurrency for 131,072 tokens per request: 2.78x

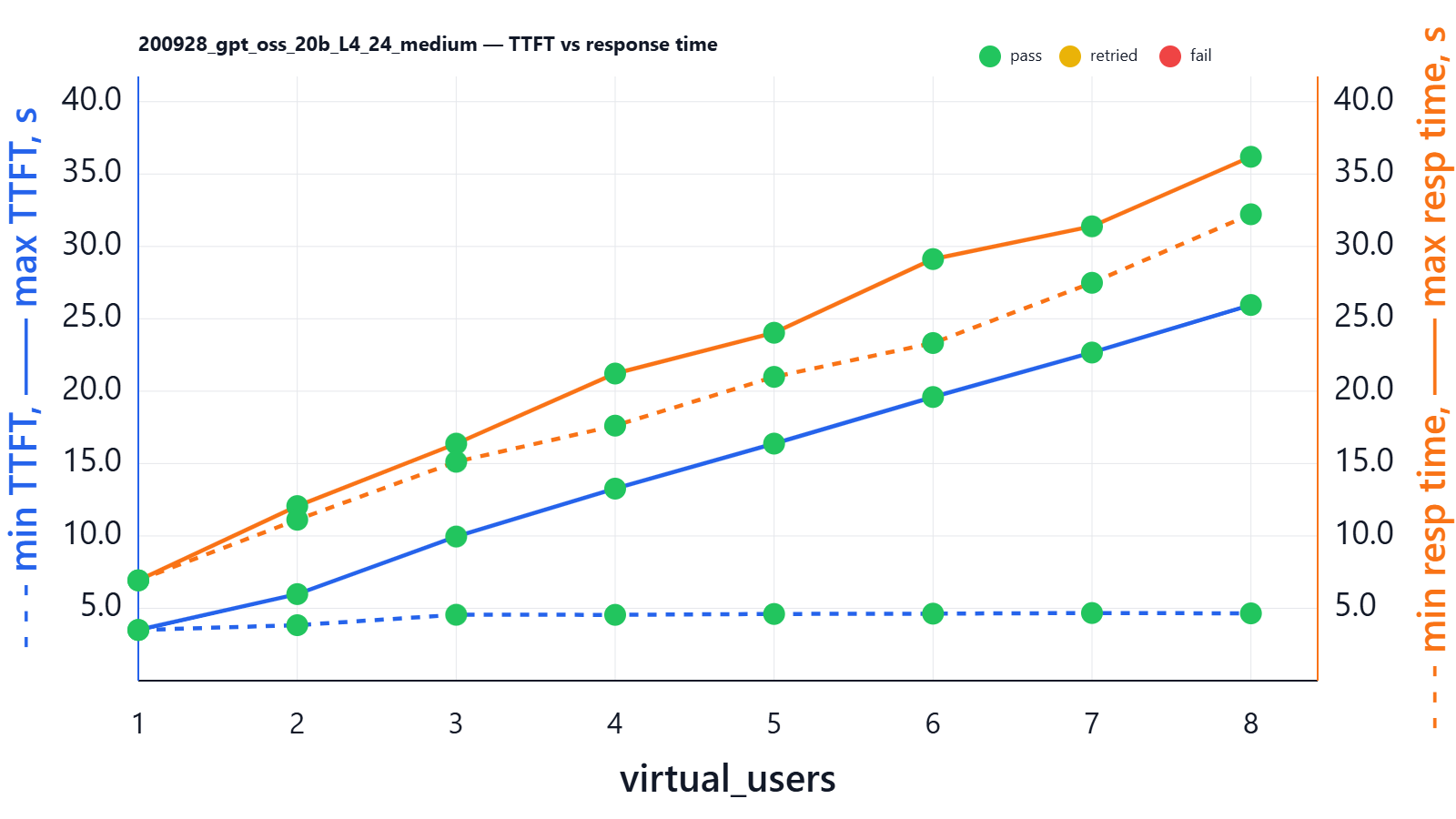

Let’s run a benchmark:

| virtual_users | min_ttft_s | max_ttft_s | min_response_time_s | max_response_time_s | Json_test_ok | secret_test_ok | nonempty_test_ok |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.502 | 3.502 | 6.932 | 6.932 | pass | pass | pass |

| 2 | 3.834 | 5.981 | 11.118 | 12.063 | pass | pass | pass |

| 3 | 4.553 | 9.957 | 15.123 | 16.375 | pass | pass | pass |

| 4 | 4.549 | 13.267 | 17.619 | 21.218 | pass | pass | pass |

| 5 | 4.609 | 16.378 | 20.988 | 24.036 | pass | pass | pass |

| 6 | 4.630 | 19.597 | 23.326 | 29.127 | pass | pass | pass |

| 7 | 4.675 | 22.669 | 27.487 | 31.389 | pass | pass | pass |

| 8 | 4.650 | 25.955 | 32.222 | 36.193 | pass | pass | pass |

With 8 parallel users, we still see that all 8 users get the final response at roughly the same time (the spread between max and min response time is ~3 seconds: the most “lucky” user gets a response in ~33 seconds and the most “unlucky” user in ~36 seconds). But the spread between the shortest and longest TTFT still grows. If the LLM is used in a chat-like interface with 8 users asking at the same time and prompts are around 10k words (e.g., include RAG and history), the chart implies that the most “lucky” user receives the first token after ~3 seconds and starts streaming, while the most “unlucky” user waits ~25 seconds for the first token.

You might ask: how, in this 8-user case, do they still receive the full response at almost the same time with such a significant TTFT spread? The large TTFT spread happens because TTFT depends on when each request gets its turn for prefill on the GPU — if a user is later in the queue, their first token simply starts later. However, once decoding begins, vLLM time-slices the GPU fairly across all active requests, so they generate tokens at roughly the same pace. The key insight is that the “unlucky” user doesn’t fall behind by the full TTFT gap, because while they were waiting, the others were not running at full speed either — they were also sharing the same GPU and spending time on prefill and other users’ work. That’s why TTFT spread can be large, but total response-time spread stays relatively small.

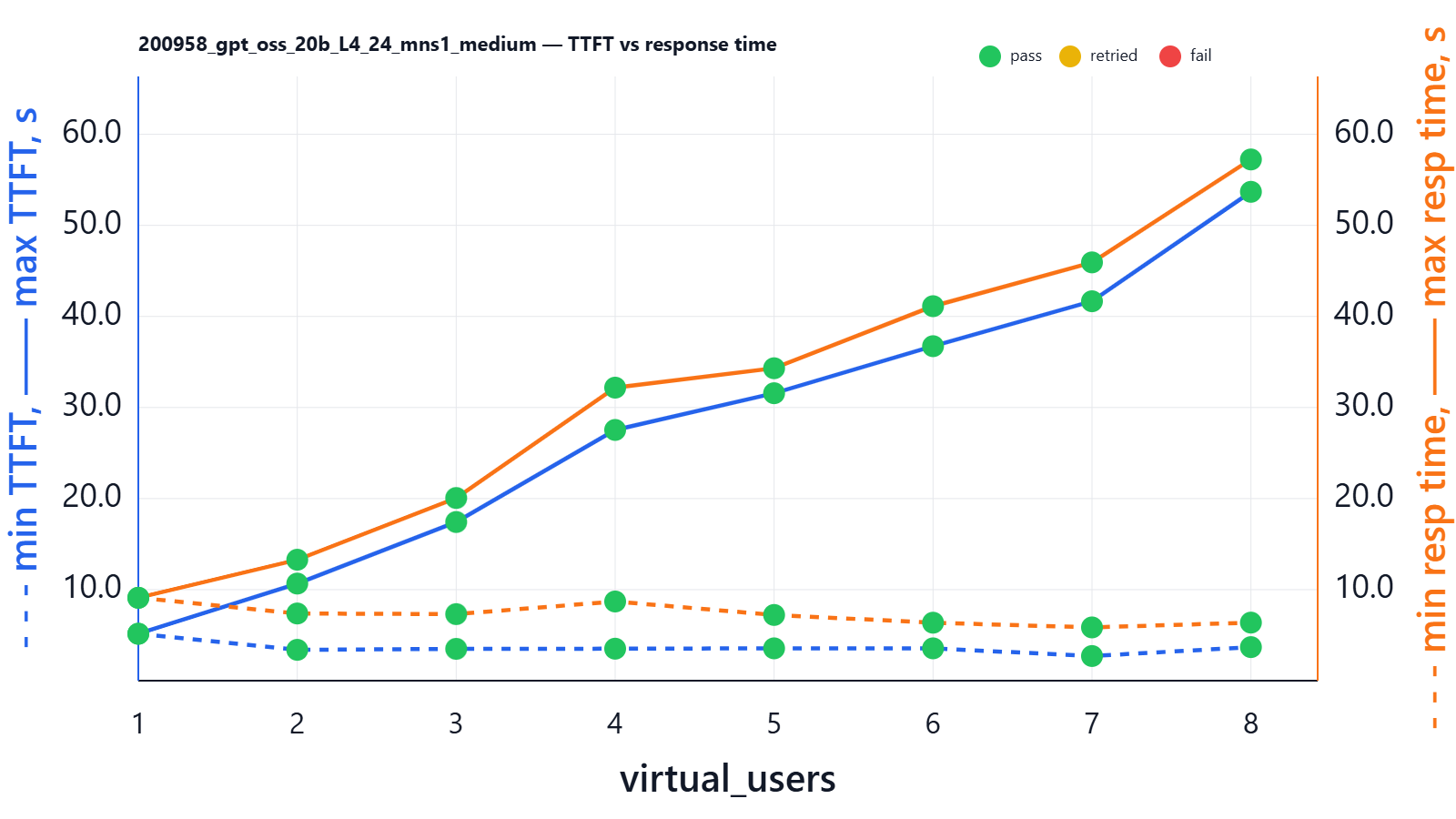

To illustrate the difference, let’s set --max-num-seqs to 1, which effectively disables parallelism:

| virtual_users | min_ttft_s | max_ttft_s | min_response_time_s | max_response_time_s | Json_test_ok | secret_test_ok | nonempty_test_ok |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.153 | 5.153 | 9.102 | 9.102 | pass | pass | pass |

| 2 | 3.387 | 10.664 | 7.379 | 13.281 | pass | pass | pass |

| 3 | 3.494 | 17.423 | 7.309 | 20.060 | pass | pass | pass |

| 4 | 3.512 | 27.533 | 8.696 | 32.178 | pass | pass | pass |

| 5 | 3.550 | 31.566 | 7.217 | 34.308 | pass | pass | pass |

| 6 | 3.550 | 36.732 | 6.366 | 41.123 | pass | pass | pass |

| 7 | 2.707 | 41.665 | 5.849 | 45.934 | pass | pass | pass |

| 8 | 3.686 | 53.682 | 6.377 | 57.237 | pass | pass | pass |

Here we see huge spreads even in total response time: with 8 users, the most “lucky” user receives the full response within ~10s, and the most “unlucky” within ~60s.

Future way to tune the model

If you wish to reduce TTFT for all requests, you can experiment by raising --max-num-batched-tokens, e.g. to 4k or 8k. By doing this, the vLLM scheduler will handle larger prefill chunks, which reduces the total number of forward passes and can reduce overall TTFT.

The drawback is that you increase the risk of VRAM OOM. Generally, VRAM OOM is less painful than RAM OOM, and Docker will gracefully auto-restart vLLM (at least it worked on my machine), but any OOM still causes downtime for a minute or so, which is definitely not good.

If you are going to change any parameters like --max-num-batched-tokens from default values, you should stress-test for OOM at the highest context and high concurrency. If you hit OOM after increasing MNBT (which is very probable), you’ll need to sacrifice something, e.g. decrease --max-model-len to 57344 tokens (56 Ki tokens = 56 × 1024).

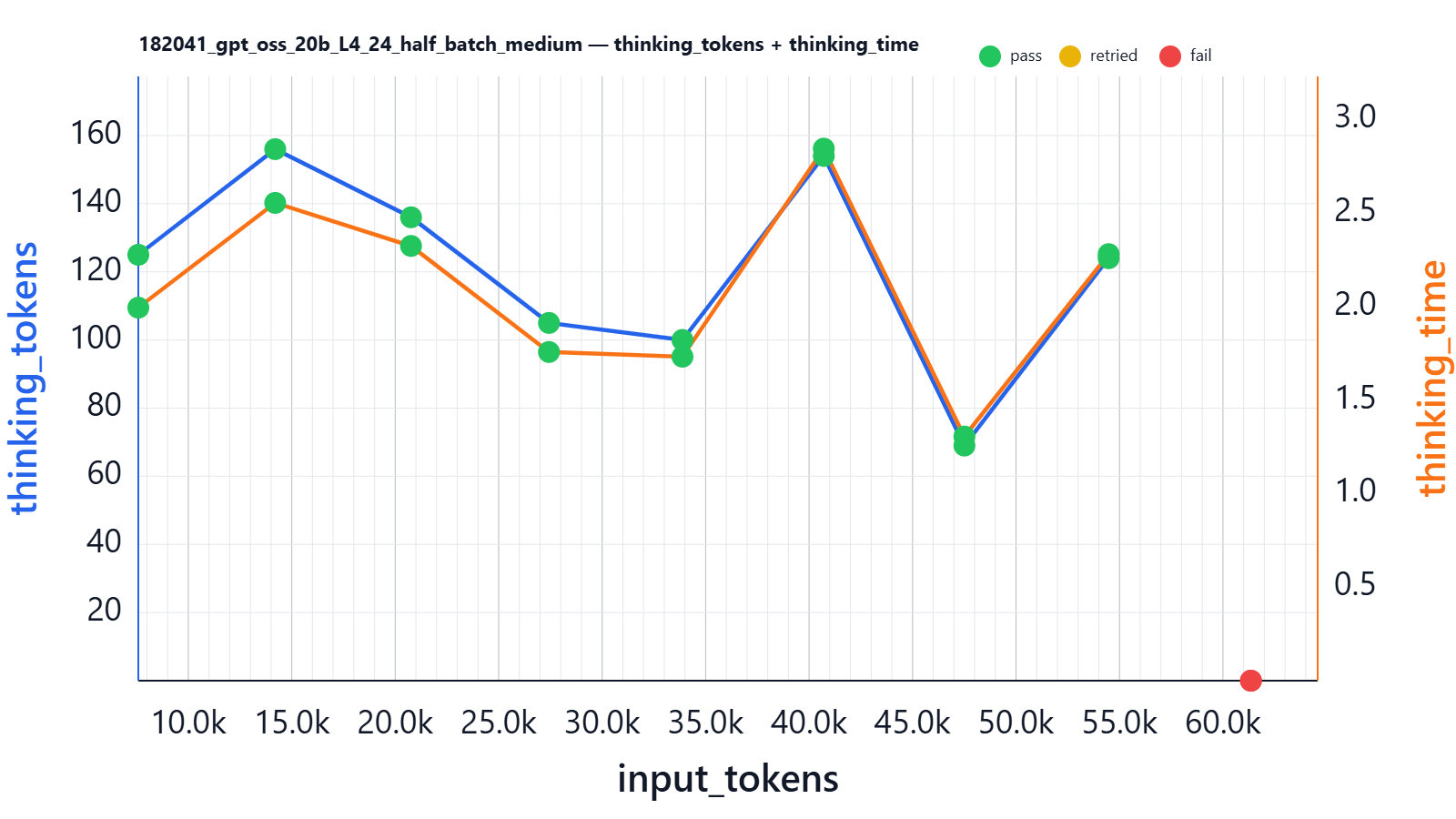

Does the model think more with more content?

In the same experiment we also fetched information about reasoning-token volumes (all experiments were executed with fixed reasoning_afford=medium):

Conclusion: thinking tokens do not depend on input size; on average the model “thinks” for about the same time (with some variance) for both 5k input words and 40k input tokens.

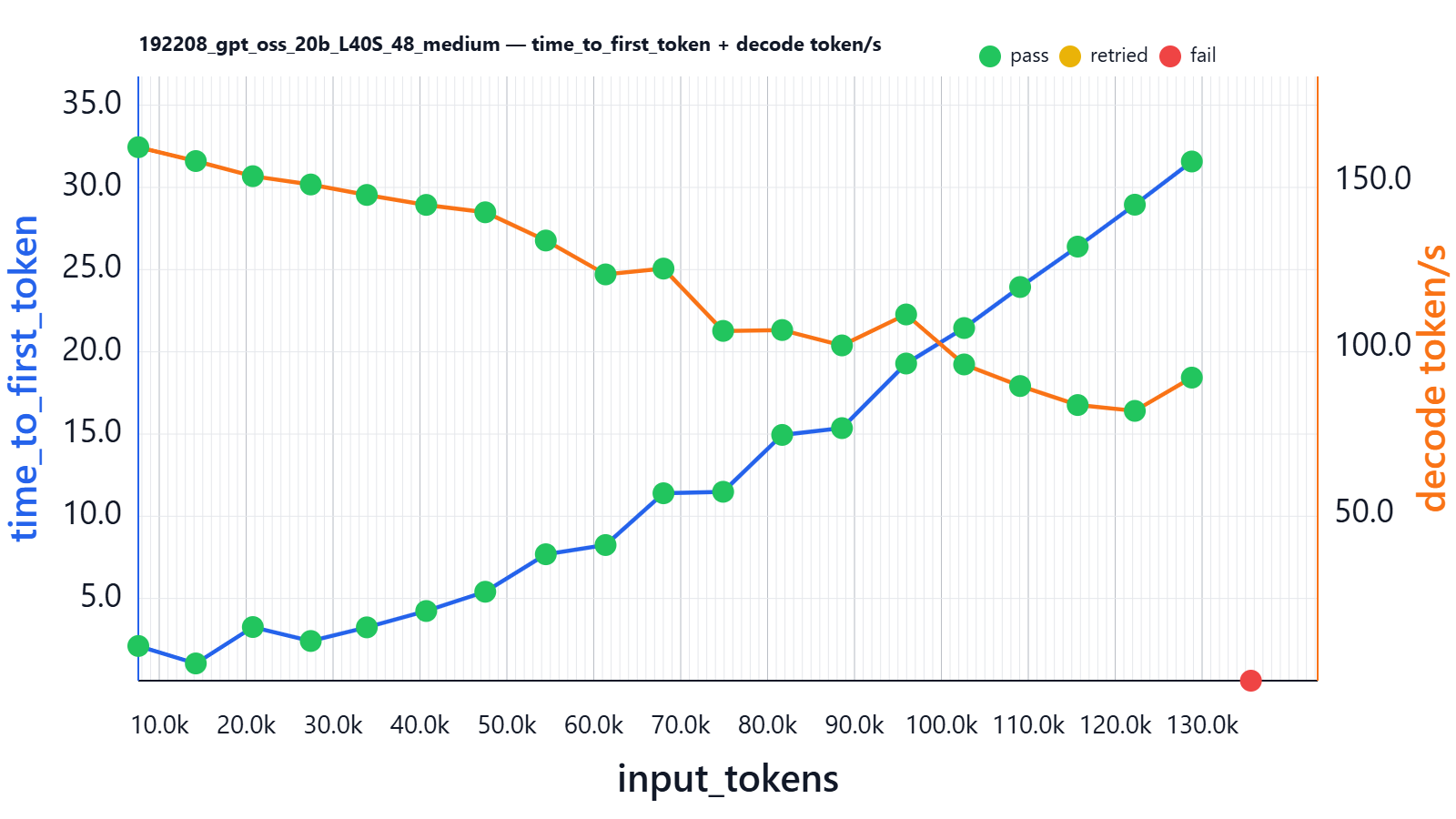

L40S 48G

Another very popular video card on the market is the L40S. Average rental price is around €1050-€1400; a new one on eBay might cost $9249 USD.

VRAM consumption is 42.112Gi/44.988Gi and stayed stable during the full experiment session.

| input_tokens | thinking_tokens | output_tokens | effective_sequence_length | time_to_first_token | decoding_tokens/s | thinking_time | Json_test_ok | secret_test_ok | nonempty_test_ok |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7589 | 76 | 64 | 7843 | 2.110 | 160.183 | 0.436 | pass | pass | pass |

| 14204 | 70 | 101 | 14437 | 1.048 | 156.022 | 0.452 | pass | pass | pass |

| 20766 | 136 | 105 | 21041 | 3.262 | 151.477 | 0.882 | pass | pass | pass |

| 27431 | 113 | 78 | 27604 | 2.414 | 148.986 | 0.690 | pass | pass | pass |

| 33883 | 120 | 82 | 34034 | 3.243 | 145.848 | 0.794 | pass | pass | pass |

| 40716 | 142 | 76 | 40820 | 4.237 | 142.857 | 0.920 | pass | pass | pass |

| 47511 | 76 | 105 | 47528 | 5.408 | 140.637 | 0.579 | pass | pass | pass |

| 54480 | 86 | 64 | 54410 | 7.690 | 132.159 | 0.650 | pass | pass | pass |

| 61355 | 191 | 77 | 61377 | 8.249 | 121.985 | 1.466 | pass | pass | pass |

| 68020 | 79 | 165 | 67950 | 11.399 | 123.732 | 0.812 | pass | pass | pass |

| 74885 | 178 | 52 | 74747 | 11.489 | 105.023 | 1.708 | pass | pass | pass |

| 81677 | 125 | 128 | 81527 | 14.947 | 105.285 | 1.322 | pass | pass | pass |

| 88557 | 125 | 117 | 88321 | 15.360 | 100.666 | 1.431 | pass | pass | pass |

| 95943 | 83 | 310 | 95792 | 19.289 | 109.961 | 1.050 | pass | pass | pass |

| 102615 | 92 | 100 | 102179 | 21.448 | 94.955 | 1.151 | pass | pass | pass |

| 109060 | 115 | 96 | 108582 | 23.942 | 88.470 | 1.483 | pass | pass | pass |

| 115679 | 132 | 121 | 115197 | 26.399 | 82.761 | 2.045 | pass | pass | pass |

| 122258 | 121 | 149 | 121742 | 28.948 | 81.008 | 2.128 | pass | pass | pass |

| 128817 | 51 | 138 | 128184 | 31.576 | 90.997 | 0.904 | pass | pass | pass |

| 135617 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | fail | fail | fail |

Here in launch log we can see that vLLM says we can run up to 16 requests on 131k sequences:

Your GPU does not have native support for FP4 computation but FP4 quantization is being used. Weight-only FP4 compression will be used leveraging the Marlin kernel. This may degrade performance for compute-heavy workloads.

Maximum concurrency for 131,072 tokens per request: 15.97x

So it is still the “Marlin” kernel, but the promised concurrency at 131k is ~16x; let’s see what it means in reality:

Here is result on our previous setup:

| virtual_users | min_ttft_s | max_ttft_s | min_response_time_s | max_response_time_s | Json_test_ok | secret_test_ok | nonempty_test_ok |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.169 | 1.169 | 1.916 | 1.916 | pass | pass | pass |

| 2 | 1.448 | 1.912 | 4.242 | 4.424 | pass | pass | pass |

| 3 | 3.112 | 4.435 | 6.415 | 6.558 | pass | pass | pass |

| 4 | 1.512 | 3.654 | 5.369 | 6.214 | pass | pass | pass |

| 5 | 1.415 | 4.550 | 6.780 | 7.647 | pass | pass | pass |

| 6 | 1.424 | 5.466 | 7.273 | 9.793 | pass | pass | pass |

| 7 | 1.439 | 6.365 | 8.698 | 9.480 | pass | pass | pass |

| 8 | 1.526 | 7.321 | 9.123 | 10.611 | pass | pass | pass |

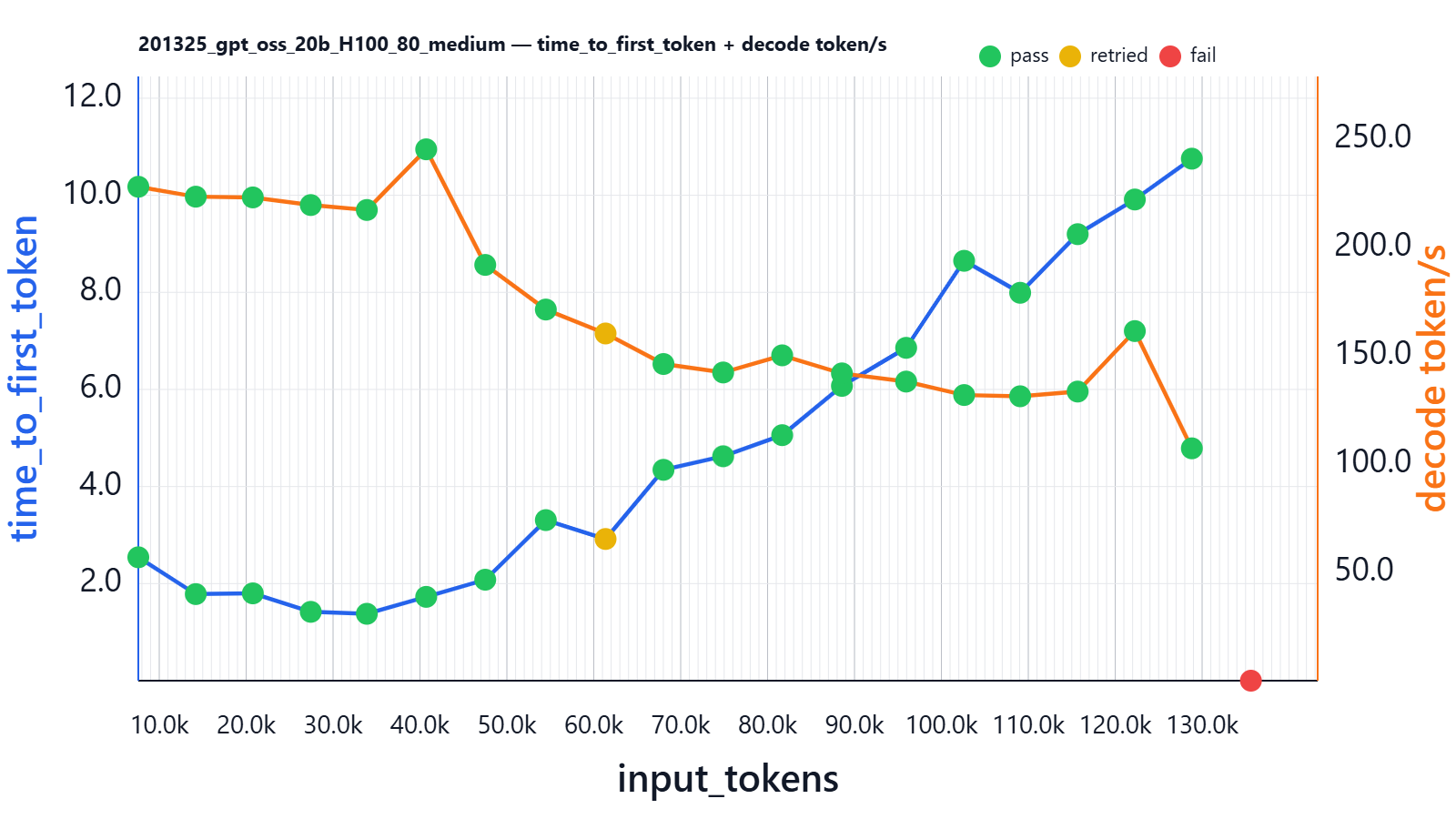

H100 80G

Typical rental price for server with H100 1x80G (varies a lot by region, PCIe vs SXM, and commitment): ~€1500–€9000 / mo. Buying one is usually ~45k depending on form factor and market.

Across the whole test run we saw VRAM up to 74.208Gi/79.647Gi, which means that with one sequence at a time the VRAM was not fully occupied.

| input_tokens | thinking_tokens | output_tokens | effective_sequence_length | time_to_first_token | decoding_tokens/s | thinking_time | Json_test_ok | secret_test_ok | nonempty_test_ok |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7590 | 121 | 62 | 7887 | 2.542 | 228.180 | 0.491 | pass | pass | pass |

| 14202 | 146 | 70 | 14480 | 1.784 | 223.602 | 0.601 | pass | pass | pass |

| 20767 | 72 | 72 | 20945 | 1.799 | 223.256 | 0.300 | pass | pass | pass |

| 27433 | 142 | 54 | 27612 | 1.418 | 219.731 | 0.604 | pass | pass | pass |

| 33885 | 110 | 52 | 33996 | 1.378 | 217.450 | 0.462 | pass | pass | pass |

| 40714 | 48 | 115 | 40763 | 1.727 | 245.482 | 0.145 | pass | pass | pass |

| 47509 | 107 | 184 | 47636 | 2.080 | 192.079 | 0.683 | pass | pass | pass |

| 54482 | 92 | 63 | 54417 | 3.308 | 171.460 | 0.589 | pass | pass | pass |

| 61355 | 106 | 86 | 61301 | 2.919 | 160.401 | 0.742 | retried | retried | retried |

| 68019 | 151 | 86 | 67942 | 4.344 | 146.296 | 1.152 | pass | pass | pass |

| 74887 | 102 | 69 | 74690 | 4.623 | 142.381 | 0.815 | pass | pass | pass |

| 81678 | 91 | 157 | 81523 | 5.058 | 150.303 | 0.863 | pass | pass | pass |

| 88554 | 68 | 91 | 88235 | 6.073 | 141.964 | 0.647 | pass | pass | pass |

| 95943 | 78 | 133 | 95611 | 6.857 | 138.179 | 0.858 | pass | pass | pass |

| 102615 | 66 | 114 | 102167 | 8.650 | 131.965 | 0.798 | pass | pass | pass |

| 109062 | 64 | 121 | 108558 | 7.991 | 131.392 | 0.782 | pass | pass | pass |

| 115678 | 46 | 108 | 115097 | 9.199 | 133.565 | 0.599 | pass | pass | pass |

| 122257 | 36 | 434 | 121941 | 9.913 | 161.512 | 0.641 | pass | pass | pass |

| 128817 | 106 | 128 | 128229 | 10.754 | 107.339 | 1.499 | pass | pass | pass |

| 135615 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | fail | fail | fail |

At the 60k point we saw the first failure, which was then successfully retried from one attempt. The issue was next, model started to repeat:

"{"main_theme":"The secret code is 314781-21","key_characters":["Ishmael","Queequeg","Captain Ahab","Captain Peleg","Captain Bildad"],\

"causal_events":[ "Ishmael leaves New Bedford","Queequeg joins him","They sign aboard the Pequod","Captain Ahab is introduced","The Pequod sets sail","The crew faces the first whale encounter","The crew confronts the great whale","The crew is pursued by the whale","The crew is rescued","The crew returns to Nantucket","The crew faces the final whale","The crew is rescued again","The crew returns home","The crew faces the final whale again","The crew is rescued again","The crew returns home","The crew faces the final whale again","The crew is rescued again","The crew returns home","The crew faces the final whale again"... and so on up to max_tokens

See details about this issue at the end of the post.

Now let’s see how it handles parallel users. In startup logs we see:

Using Triton backend

Maximum concurrency for 131,072 tokens per request: 31.52x

This is a first model using Triton with native fp4 support.

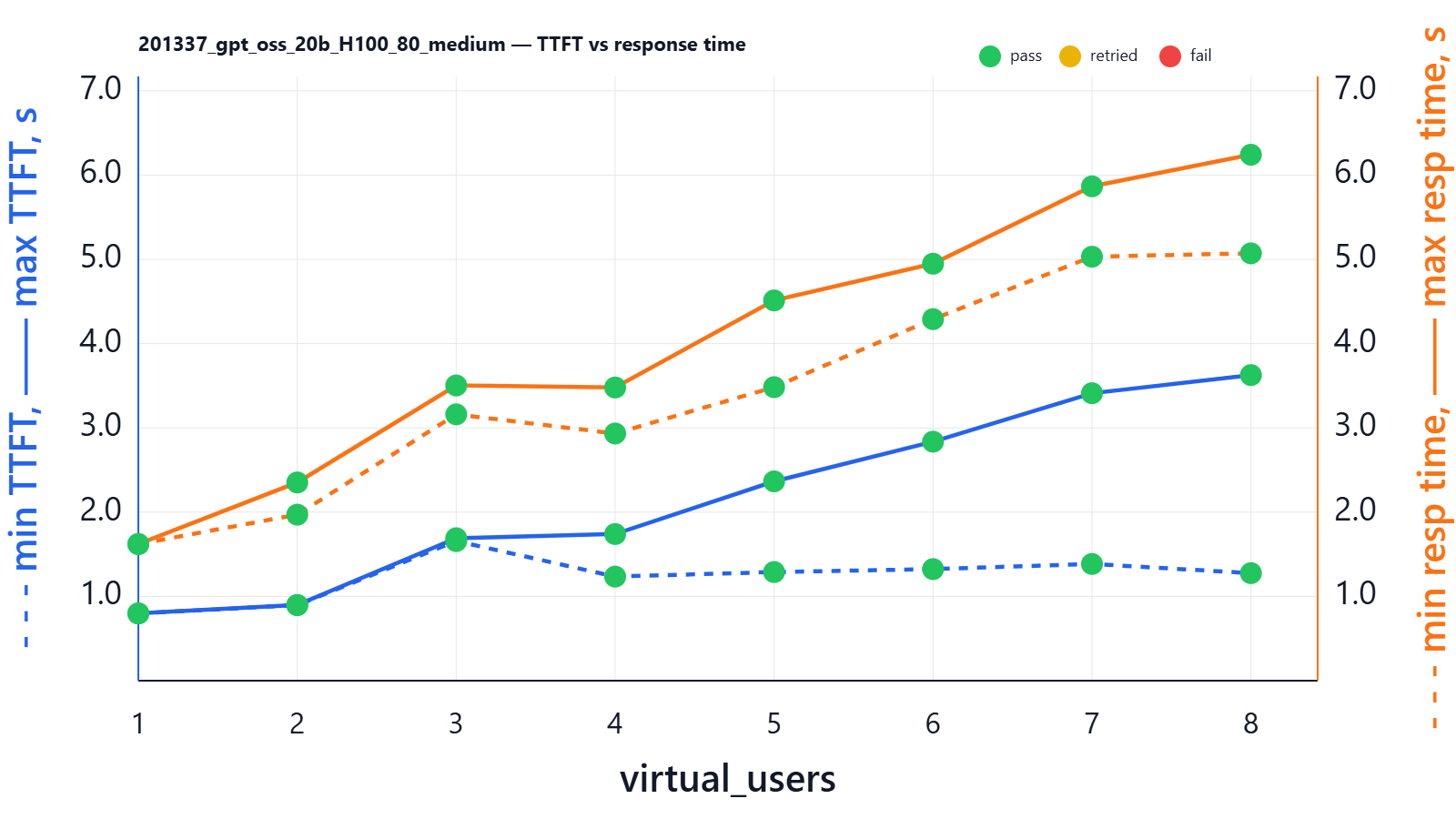

| virtual_users | min_ttft_s | max_ttft_s | min_response_time_s | max_response_time_s | Json_test_ok | secret_test_ok | nonempty_test_ok |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.798 | 0.798 | 1.621 | 1.621 | pass | pass | pass |

| 2 | 0.896 | 0.898 | 1.970 | 2.352 | pass | pass | pass |

| 3 | 1.657 | 1.690 | 3.160 | 3.503 | pass | pass | pass |

| 4 | 1.235 | 1.740 | 2.933 | 3.479 | pass | pass | pass |

| 5 | 1.289 | 2.365 | 3.483 | 4.512 | pass | pass | pass |

| 6 | 1.324 | 2.836 | 4.290 | 4.948 | pass | pass | pass |

| 7 | 1.385 | 3.411 | 5.031 | 5.866 | pass | pass | pass |

| 8 | 1.276 | 3.626 | 5.071 | 6.241 | pass | pass | pass |

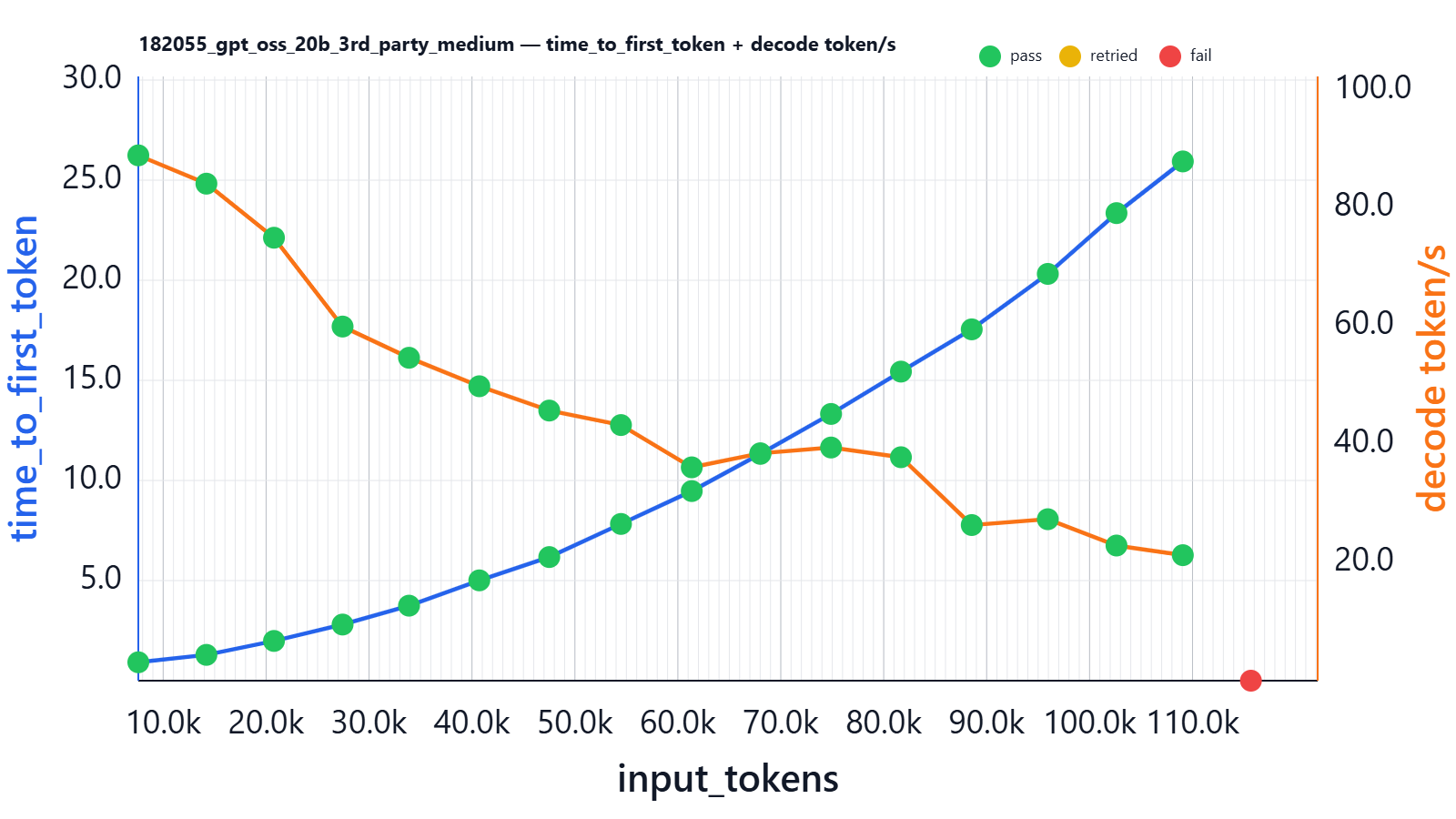

Managed gpt-oss-20b hosting

Some hosting services nowadays provide inference-as-a-service. For example, they may host gpt-oss-20b for you, so you pay for used tokens instead of paying for a whole server running 24/7. This can still be cheaper than many official vendor LLMs, but again the risk of data exposure is high if you don't sign dedicated DPAs.

Generally they don’t disclose what hardware they use under the hood or what vLLM parameters they run.

| input_tokens | thinking_tokens | output_tokens | effective_sequence_length | time_to_first_token | decoding_tokens/s | thinking_time | Json_test_ok | secret_test_ok |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7585 | 134 | 77 | 7913 | 0.919 | 88.888 | 1.538 | pass | pass |

| 14199 | 138 | 103 | 14506 | 1.289 | 84.099 | 1.599 | pass | pass |

| 20764 | 82 | 88 | 20972 | 1.985 | 74.951 | 1.174 | pass | pass |

| 27429 | 102 | 93 | 27610 | 2.804 | 59.921 | 1.800 | pass | pass |

| 33881 | 150 | 87 | 34069 | 3.747 | 54.639 | 3.151 | pass | pass |

| 40712 | 79 | 90 | 40771 | 5.011 | 49.820 | 1.841 | pass | pass |

| 47507 | 87 | 88 | 47522 | 6.175 | 45.707 | 2.200 | pass | pass |

| 54475 | 182 | 87 | 54527 | 7.829 | 43.253 | 4.825 | pass | pass |

| 61351 | 91 | 84 | 61284 | 9.472 | 36.097 | 3.006 | pass | pass |

| 68016 | 92 | 90 | 67887 | 11.330 | 38.478 | 2.824 | pass | pass |

| 74882 | 46 | 96 | 74660 | 13.323 | 39.453 | 1.876 | pass | pass |

| 81673 | 79 | 88 | 81441 | 15.438 | 37.809 | 2.651 | pass | pass |

| 88551 | 87 | 125 | 88288 | 17.549 | 26.334 | 4.732 | pass | pass |

| 95939 | 97 | 132 | 95628 | 20.319 | 27.321 | 4.479 | pass | pass |

| 102614 | 90 | 101 | 102180 | 23.355 | 22.869 | 5.336 | pass | pass |

| 109059 | 55 | 160 | 108587 | 25.937 | 21.237 | 4.751 | pass | pass |

| 115674 | 106 | 1430 | 116479 | 0.000 | 41.197 | 6.034 | fail | fail |

What we can see from this chart:

- For short sequences, the best decoding throughput was better than on L4 (~80 tokens/s), but worse than on L40S and H100 in our setup.

- Time to first token is nearly the same as on L40S (e.g., ~5s at ~40k input tokens), but our H100 setup is better.

How does it handle parallel users?

We see that 3rd-party hosting keeps delay at a good level and it does not significantly degrade as the number of users increases. When you are using LLM-as-a-Service endpoints, you can generally run as many sequences (API requests) as you need in parallel and can expect them to generate in parallel. This is possible because the external provider has a horizontally scalable (from your perspective, effectively infinite) pool of GPUs and can split API requests from many clients. Obviously they split the payload across multiple inference endpoints to achieve maximum efficiency.

Structured output failure due to degenerate repetition

Since we had one retried case on H100, after running the main experiments, we stress-tested the model by running at peak points for half an hour.

And very rarely we see retries caused by broken JSON:

{

"main_theme": "Moby-Dick",

"key_characters":[ "Ishmael","Queequeg","Captain Ahab","Captain Peleg","Captain Bildad","Father Mapple"],

"causal_events":[ "Ishmael leaves New Bedford for Nantucket","Ishmael meets Queequeg at the Spouter‑Inn","Ishmael and Queequeg sign aboard the Pequod","Captain Ahab’s leg is lost to a whale","The Pequod sets sail","The crew encounters the great white whale","The crew is pursued by the whale","The crew is rescued by the crew of the ship “The Rachel”","The crew is pursued by the whale again","The crew is rescued by the crew of the ship “The Delight”","The crew is pursued by the whale again"....

This issue was always successfully retried on the next attempt.

Its frequency is quite low: we saw from 1 to 5 occurrences during 30 minutes, but this frequency may depend, for example, on the entropy and lengths of incoming prompts.

This issue happened at any point of any experiment, and this may be a common picture for the GPT-20B model.

Moreover, this issue happens with any LLMs. Gemini, for example, quite often goes into this repetition even in the public UI, while OpenAI might hide it via retries (it’s quite easy to detect repetitions).

Attempts to run gpt-oss-120B on H100 80G

In theory, 80G might be enough to run even a 120B model. Its weights in MXFP4 consume at least 60GB by definition (in fact I’ve seen 64.38 GiB in logs - some CUDA overhead), so what’s left for KV cache and activations is much less than 14G, which is very tight assuming the number of layers in this model is higher.

Default parameters for this model on Hugging Face / vLLM are definitely not optimized for 80G VRAM:

| MML (max-model-len) | 131072 | | MNBT (max-num-batched-tokens) | 8192 | | MMU (gpu-memory-utilization) | 0.9 | | MNS (max-num-seqs) | 256 |

With these settings the model does not load at all:

Model loading took 64.38 GiB memory

Available KV cache memory: -0.62 GiB

Setting MNBT to 2048 still did not help. So with the same config as we used for 20B on 24G VRAM, we can’t run 120B on 80G VRAM.

The reason 120B cannot start on a single H100 80GB with the same 131k context settings that worked for 20B is that KV cache memory scales with the number of layers and the hidden size of the model, not just with available VRAM. While 20B left ~10GB for KV cache on a 24GB GPU, the 120B model has roughly 4–5× larger per-token KV footprint due to significantly more layers and a much larger hidden dimension. So even though ~16GB appears “available” after loading weights on H100, each token now consumes far more KV memory, making a 131k context mathematically infeasible on a single GPU.

Reducing --max-model-len to half (e.g. 57344) didn’t help either. You can probably extract something from this card by reducing values even more, but it will be very limited and needs careful OOM testing. Ideally you should use 2× H100 80G and set --tensor-parallel-size 2.

Conclusion

At a typical “real” chat/RAG workload size (≈10k input words: history + retrieved context + a short user question like “Given the attached policy and our last 5 messages, what are the top 3 risks and the next steps?”), the single-user latency for gpt-oss-20b differs dramatically by GPU. In our 1-user run at that prompt size, L4 24G delivered ~3.50s TTFT and ~6.93s full response time, L40S 48G ~1.17s TTFT and ~1.92s full response time, and H100 80G ~0.80s TTFT and ~1.62s full response time.

If your system is used frequently by many people (for example, an internal chat tool where several employees ask questions at the same time), the same ~10k context request can be in-flight concurrently. With 5 parallel users at this prompt size, we observed that L4 24G spreads TTFT from ~4.61s (lucky) to ~16.38s (unlucky) and full response time from ~20.99s to ~24.04s; L40S 48G keeps TTFT in ~1.42–4.55s and full response in ~6.78–7.65s; and H100 80G keeps TTFT in ~1.29–2.37s and full response in ~3.48–4.51s. In practice this matters because user-perceived latency is dominated by TTFT in streaming UIs, and concurrency is the normal case for shared tools.

From a cost-efficiency standpoint, L4 is the cheapest entry point (and works well for low concurrency), but it becomes latency-limited quickly as context grows. L40S is often the sweet spot for gpt-oss-20b: it cuts single-user latency by ~3–4× versus L4 while typically costing less than 2×, and it also provides substantially more parallelism headroom at long contexts. H100 wins on raw latency and concurrency, but unless you specifically need the lowest possible tail latencies at higher load, it is usually harder to justify purely on €/latency for a 20B-class model.

Useful links

- Free Lab Chat Demo where you can evaluate the quality of answers of gpt-oss-20b and other models on your own prompts and PDF documents.

- Optimization and Tuning of vLLM clearly describes main tuning ideas.

- A must LLM Terminology to understand this post explains all the terms used in this post.

- gpt-oss-20b on Hugging Face