LLM Terminology Guide: Weights, Inference, Effective sequence length, and Self-Hosting Explained

A clear guide to generative AI and LLM terminology. Learn how model weights, quantization, inference, context length, batching, sampling and many more — including how to evaluate vendor APIs and self-host models like GPT-OSS-20B.

Generative AI and LLM terminology can feel overwhelming — especially when considering self-hosting open-weight models like GPT-OSS-20B.

This practical guide explains the core concepts every technical decision-maker, product owner, and engineer should understand: model weights (parameters), inference, context length, KV cache, tokenization, batching, streaming, and structured output.

Whether you're deploying your own inference stack with open-source servers like vLLM, this overview provides the foundational vocabulary required to make informed architectural and cost decisions.

If you're evaluating AI adoption at an SMB or enterprise level, this glossary equips your team with the terminology needed to compare solutions confidently, understand pricing models, and assess infrastructure trade-offs — from API usage to self-hosted deployments.

Terms

What is a token?

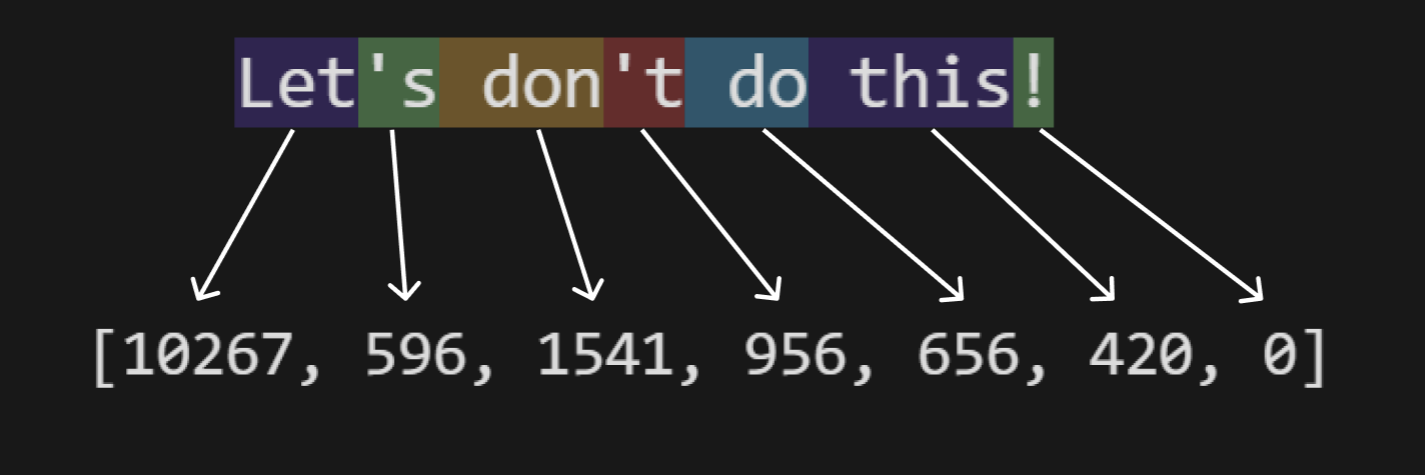

All text is encoded into tokens (tokenized) before being sent to an LLM. Each token is just a number.

As a rule of thumb, you can think of it as “one word + the whitespace after it” becoming one token, with exceptions (for example, Don't may be split so that 't becomes a separate token).

Here’s a real example using the OpenAI tiktoken tokenizer (GPT-4/3.5-like):

In real life, you can use the following ratios as a rough average (this is approximate, and reasonably aligned with the tiktoken behavior used by GPT-OSS-20B/120B):

- In English: 1 word ≈ ~1.3 tokens

- In Ukrainian: 1 word ≈ ~1.6 tokens

- In German: 1 word ≈ ~1.8 tokens

You send tokens to the model (input); the model completes them with new tokens (generated); then you decode the tokens back into text.

What are model weights (parameters)

Trained values learned during the training process. During usage, they are loaded into video RAM (VRAM).

All open-source models specify how many parameters they have, usually measured in billions (e.g. 6b, 20b, 120b).

On average, a higher parameter count can mean “better,” but it also requires more compute and memory.

What is LLM inference

The actual use of a model: a trained model loaded into VRAM generates a response. Inference does not change the model parameters.

What is Hugging Face

A website where anyone can publish weights for open-source (open-weight) models along with configuration files.

Inference is technically performed by other open-source software such as the transformers Python package, vLLM, or TGI.

These tools load weights (often downloading them over the network at launch because the weights are large).

What is an LLM sequence

A single independent stream of tokens (prompt + generated tokens) processed by the model as one attention context during inference.

Sometimes developers call it a “request,” and from an API perspective one API request generally creates one sequence.

But from the LLM perspective, it’s still a sequence.

Effective sequence length

The sum of all input tokens and generated tokens produced during inference. If you send 10 tokens to the model and receive 5 back, then ESL = 15 tokens.

Context Window

The hard technical limit on effective sequence length (defined by the model’s architecture and internal data structures).

Maximum

effective sequence lengthshould be less thancontext_window.

In reality, there are circumstances (mostly resource limits, discussed later) that effectively change this rule to:

Maximum

effective sequence lengthis much less thancontext_window.

There is an interesting pitfall: many ESL/context parameters nowadays are denoted in thousands of tokens.

For example gpt-oss-20b has a context window equal to 131072 tokens. This is an exact value, but it is not easy to write all 6 digits, so the community uses shorter forms.

| 131072 tokens | ✅ True, original value |

| 131k tokens | ✅ Means the same. k = kilo in SI, but this is approximate; the real value is 131.072k |

| 128Ki tokens | ✅ The same value: 128 × 1024 = 131072. This is the correct binary prefix |

| 128k tokens | ❌ This is a very typical mistake. 128k is 128000, and this is not 131072. For decades, engineers struggled with the ambiguity of “kilo” in data sizes and eventually introduced binary prefixes like Ki, Mi, and Gi to fix it — and now, in this new niche we’re stepping on the same rake again, this time with tokens. Don't trust developers who say the context window of GPT-OSS-20B is 128k; it is 3k higher. |

Reasoning vs Non-reasoning models

They differ in how the model is trained.

Reasoning models are trained and fine-tuned to perform reliable multi-step reasoning, rather than relying only on pattern matching or surface-level completion.

For example, a non-reasoning Question (Q) / Answer (A) training sample might be:

Q: If John is older than Mary and Mary is older than Tom, who is the oldest?

A: John.

A reasoning training sample might be:

Q: If John is older than Mary and Mary is older than Tom, who is the oldest?

A: John is older than Mary.

Mary is older than Tom.

Therefore, John is older than both Mary and Tom.

**So John is the oldest.**

For math tasks, reasoning is crucial:

Q: A train travels 60 km in 1 hour. How far in 3.5 hours?

A: 180 km.

Here, the model can memorize the answer and fail to generalize to similar tasks. In a reasoning-optimized setup, the model learns the steps so it “knows” how the answer is formed:

A: 60 km/h × 3.5 h =

60 × (3 + 0.5) =

180 + 30 = 210 km.

Non-reasoning models can still answer instantly (and may be correct), but for multi-step logic and math they’re more likely to be wrong.

Reasoning models emerged around 2022–2024 as LLMs began being optimized not just to generate fluent text, but to reliably perform multi-step logical inference, significantly improving performance in math, coding, and complex analytical tasks.

OpenAI GPT-OSS-20B/120B, DeepSeek R1, and Qwen 3/2.5 OSS models are reasoning models. GPT-J and LLaMA v1/v2 are commonly treated as non-reasoning models.

During inference, the model may also output “thinking” tokens. The obvious drawback is a higher effective sequence length, and we know it is limited.

vLLM

vLLM is an open-source inference server that lets companies run large language models on their own hardware and expose them as production-ready AI APIs.

For reasoning models, it performs an important task: splitting the reasoning (“thinking”) stream from the final answer stream via special string parsing (usually quite reliably).

Think of it as:

“OpenAI-style endpoint for your own models.”

Technically, you specify the model name on Hugging Face (a website hosting open models). If it’s a supported decoder-only Transformer model, vLLM downloads the weights (parameters) and loads them into VRAM. During inference, vLLM encodes the sequence into tokens, maps them into a vector space, processes them with the model parameters, and generates new tokens.

What is Quantization

Quantization is an optional post-processing step (often done by third parties) that reduces how many bytes are used to store each model parameter in VRAM.

Most open-source models are published in BF16 (16-bit floating point), meaning:

1 parameter = 2 bytes

So a 32B model needs roughly:

32B × 2 bytes ≈ 64 GB VRAM

Quantization lowers precision (for example to 8-bit or 4-bit), which proportionally reduces memory usage. A 32B model in 4-bit would consume ~16 GB instead of 64 GB.

Most open-source quantization is done after training (BF16 → INT8 / INT4 / etc.). This makes models much cheaper to run, but may slightly reduce reasoning stability, especially for long logical chains or structured outputs.

Lower precision = cheaper and faster inference.

Higher precision = more stable and reliable reasoning.

It’s important to note that “4-bit parameters” does not always mean the model was quantized after training. For example, OpenAI GPT-OSS-20B/120B are trained to run in a 4-bit format and can be more stable than a community-quantized model that started from wider (BF16) ranges.

Reasoning effort

reasoning_effort is an inference-time parameter that controls how long a model generates reasoning tokens before giving its final answer.

For example, in GPT-OSS-20B/120B, vLLM modifies the system-level instruction (Harmony format), which shifts token probabilities and leads to shorter or longer reasoning chains.

Other models may use different mechanisms than system-level instruction (e.g. logit biasing around “Final” / “Answer” tokens).

Lower reasoning_effort produces fewer thinking tokens, reducing effective sequence length, which can improve latency and memory efficiency.

Not all reasoning-capable models support reasoning_effort, because dynamic control of reasoning depth requires specific training support.

Concurrent (parallel) sequences

When you use an LLM-as-a-Service endpoint, you can usually run as many sequences (API requests) in parallel as you need and expect them to generate concurrently.

This is possible because the external provider has a horizontally scalable (from your perspective, effectively “infinite”) pool of GPUs and can spread requests across them.

In self-hosted setups, when you have one GPU (or a small number of GPUs), throughput is limited.

In practice, you can run one or several sequences. In a vLLM Docker container this is controlled by the --max-num-seqs X parameter.

If you run with --max-num-seqs 1 and you send 2 API requests at the same time, the second will be queued by vLLM and will wait for the first to finish.

If you run with --max-num-seqs 2, then 2 requests can start at the same time and be handled in parallel. However, the effective sequence length you can afford may be lower (explained below).

So when the max number of sequences is low, you get lower throughput (e.g. teammates wait longer when using the service concurrently).

What is OpenAI gpt-oss-20b and 120b

Two open-source models that OpenAI published in the second half of 2025.

Both models are trained on mxfp4 (each parameter takes half a byte), meaning the 20b version takes about 10 GiB of VRAM for weights, and the 120b version takes about 60 GiB.

This is only the weights. In practice there is overhead, and the sequences themselves must also live in VRAM (both input tokens and generated tokens).

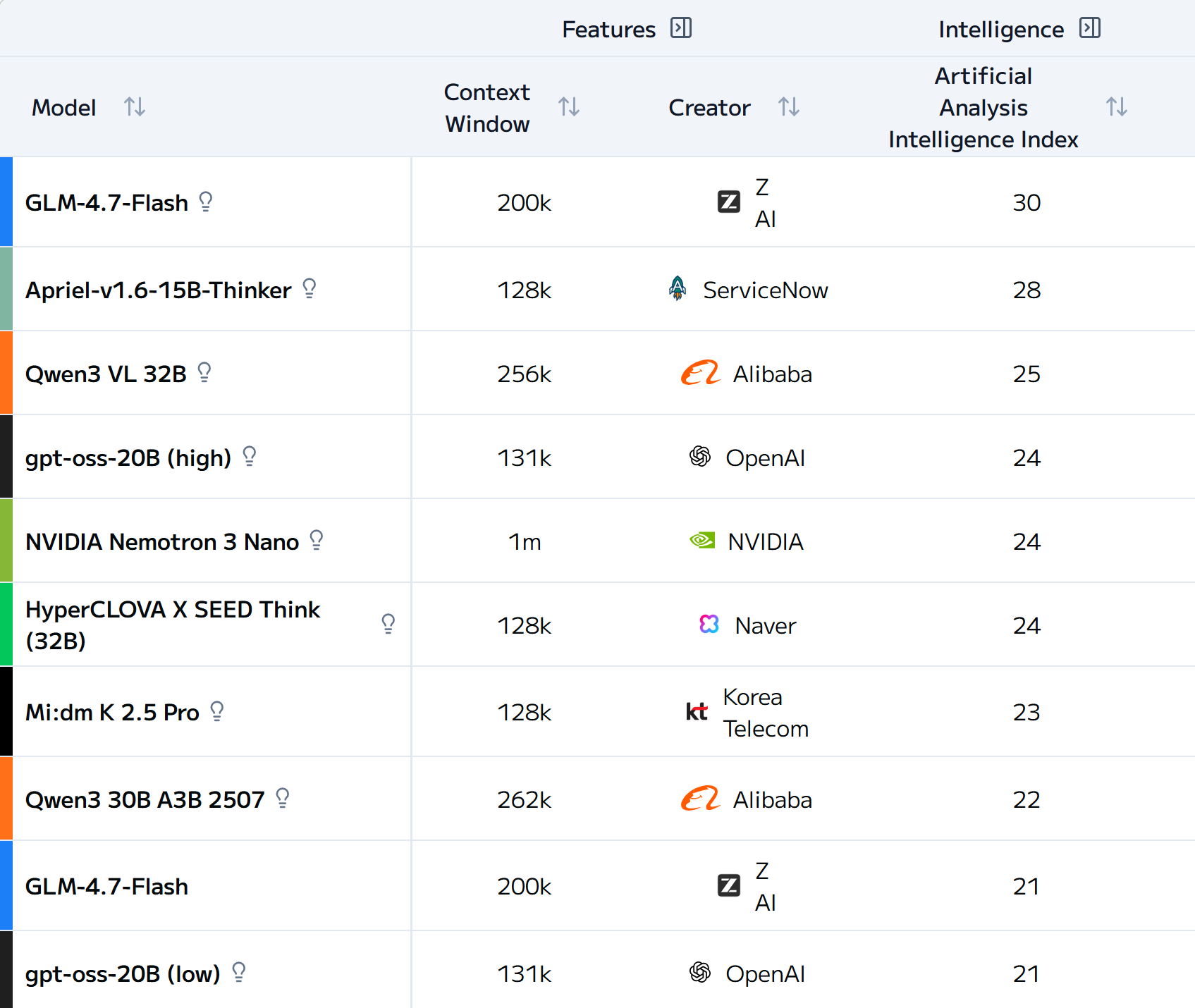

As of today (Feb 2026), 120b in high-reasoning mode has AAII = 33 in the top Medium-size models (up to 150B params).

GLM-4.7is30b × BF16and consumes ~60 GBVRAM.Apriel-v1.6-15B-Thinkeris15b × BF16and consumes ~30 GBVRAM.Qwen 3 VLis32b × BF16and consumes ~64 GBVRAM.

Although all three models are larger than gpt-oss-20b, community quantizations are available — in some cases down to 4-bit precision.

However, post-training community quantization (e.g., compressing BF16 weights to FP4/INT4 after training) generally produces less stable and less predictable results compared to models architected and optimized for low-precision inference from the start (e.g., OpenAI’s MXFP4-style formats). So working with community quantization may require additional research. AAII covers only the original, non-quantized versions.

How an LLM actually works (simple and short)

There are a few more terms that are easier to understand once you see the actual model workflow.

The user sends a REST request to a vLLM-like server that already has the model weights loaded into GPU VRAM.

All input text is tokenized into numbers.

These token IDs are passed to the model, where each token is mapped into a latent vector space.

This mapping is done via a simple lookup operation in a learned matrix called the embedding matrix (size of vocabulary), which is part of the model parameters (relatively small compared to the full model). You can think of this as a parallel lookup for each token, which is very fast.

For GPT-OSS-20B, each embedding vector has 6144 dimensions. If the model weights are stored in a 4-bit format, these values are typically dequantized to BF16 before computation, because subsequent matrix multiplications generally aren’t performed directly in 4-bit precision.

Vector directions in this high-dimensional space encode semantic meaning. For example, vectors for tokenized words like kid and child will be close to each other, and the cosine similarity between them will be close to 1.

The main goal of a forward pass is to transform the last token’s representation so it aligns with the most probable next token, given all previous tokens (including structure and relationships).

During inference, token vectors are projected through learned weight matrices: the Key, Value, and Query matrices. The projection of a token vector is performed by multiplying the vector by each of the three learned matrices (K, V, Q). The temporary result of any internal operation (e.g., Q, K, or V projections) is called an activation. The Q and K activations are used to compute attention scores, which determine how much each token should attend to others, and these scores are applied to the V activations to produce a weighted combination of token information. This is called the attention mechanism, which determines how strongly tokens influence one another. This is the core innovation of the Transformer architecture introduced by Google Brain in 2017. The result of attention is then projected back to the model’s hidden vectors using an additional learned output projection matrix (often denoted Wo).

After attention, token representations are updated with contextual information. Each token vector then passes through a feed-forward network (FFN) with a nonlinear activation function, which further refines the representation.

This process repeats sequentially across many Transformer layers. Each layer refines contextual understanding and extracts higher-level structure.

At the final layer, the last token representation is projected into a vector of scores (logits) over the entire vocabulary. These logits are converted into probabilities (e.g. from 0.001 to 0.999). In practice, to get logits, the GPU computes dot products between the final hidden vector of the last token in the sequence and all embedding vectors (or a tied output matrix) to obtain scores for every token in the vocabulary. You can think of this as measuring how aligned two vectors are — similar to cosine similarity. The more aligned they are, the higher the score.

So logits are probabilities of similarity of the resulting vector on the last token to every token in the vocabulary. The logits array size is equal to the number of tokens in the vocabulary, but most times only a few elements have high probabilities; most are close to 0.

The full computation cycle where all input tokens are set, producing final logits on the last token, is called a forward pass.

vLLM then selects the next token using sampling. By default, this behaves like weighted random selection: if one token has a much higher probability, it’s more likely to be chosen.

API parameters influence sampling:

-

Temperature reshapes the probability distribution. Higher temperature makes probabilities more uniform; temperature 0 results in greedy (most probable) selection.

-

top_p filters tokens to the smallest cumulative probability mass.

-

top_k limits selection to the top K tokens.

Selecting the next token is called sampling.

So after sampling, one forward pass produces one token. That token is appended to the input sequence, and the process repeats. That is why the context window is a total limit of all input and output tokens, and not only input tokens as someone might think.

Production optimizations

Thanks to the Transformer architecture, previously computed Key and Value activations can be stored in the KV cache (in VRAM). This avoids recomputing them at each step and significantly speeds up generation.

The process of generating the first token of a sequence is called prefill. This is the most computationally heavy operation because at this step activations for Q, K, and V are formed for all input tokens. K and V are cached, while Q will not be needed anymore and can be discarded after the step is finished.

When the first token is generated, it is added to the sequence. Now the sequence has K and V cached for each of the previous tokens, and for the new token we compute fresh Q, K, and V (only for this single token). The new K and V are added to the cache for future steps. As a result, the 2nd token is generated much faster. The same applies to the 3rd token and so on.

New tokens start appearing so fast that they can even be streamed to the frontend (e.g., via SSE or WebSocket) in chat UIs. This phase is called decoding.

Prefill = first, slow, compute-heavy, VRAM-consuming.

Decoding = fast.

The time from the start of the sequence to the appearance of the first token is often called Time To First Token (TTFT). While it is very close to prefill duration, TTFT may also include small additional overhead (such as sampling or scheduling).

After a sequence is finished, the KV cache is not necessarily removed immediately. In systems like vLLM, prefix caching allows previously computed KV blocks to be reused if a new prompt shares the same prefix. KV memory is managed using the LRU principle — when VRAM space is needed, old cache blocks are evicted. If space is still available, cached prefixes can be reused efficiently.

This is especially effective for agents or chat systems that share a common system prompt at the beginning.

Batching & Chunking

If several small sequences are evaluated, vLLM can group them into one forward pass. So batch size is the maximum number of input sequences that will go into prefill. Batch size limits only the sum of input tokens; decoding happens on top of it.

The same can be applied in reverse: if a sequence is too large, vLLM can split it into smaller chunks (using the same batch size limit). This way VRAM spikes needed for activations are limited (a common practice to avoid OOM). But of course it will increase the number of forward passes and time to first token.

Conclusion

If you’re evaluating or self-hosting open-weight LLMs, the most important mental model is that everything becomes tokens, and both cost and latency scale with how many tokens you process.

In practice, your deployment constraints are dominated by two things:

- VRAM, which must hold the model weights plus KV cache for all concurrent sequences.

- Effective sequence length, which grows with longer prompts, longer answers, and especially with reasoning (“thinking”) tokens.

Once you understand tokens, context windows, KV cache, quantization, and concurrency controls (like --max-num-seqs in vLLM), you can compare API providers vs self-hosted setups more confidently and make clearer trade-offs between quality, throughput, and infrastructure cost.